When asked about his favorite poems, Pierre Joris replied with Paul Celan’s “Line the wordcaves” from Fadensonnen / Threadsuns.

LINE THE WORDCAVES

with panther skins,

widen them, hide-to and hide-fro,

sense-hither and sense-thither,

give them courtyards, chambers, drop doors

and wildnesses, parietal,

and listen for their second

and each time second and second

tone.

KLEIDE DIE WÖRTHOHLEN AUS

mit Pantherhäuten,

erweitere sie, fellhin und fellher,

sinnhin und sinnher,

gib ihnen Vorhöfe, Kammern, Klappen

und Wildnisse, parietal,

und lausch ihrem zweiten

und jeweils zweiten und zweiten

Ton.

I have been reading & translating Paul Celan’s work for many years—close to fifty, in fact. His work is always complex & difficult, and theerfore I often turn to the poem above—“Line the wordcaves” from the volume Fadensonnen / Threadsuns—because, besides being a fascinating & well-made poem, it is also a programmatic meta-poem. It give us a handle on how to approach such poems by foregrounding how the poet envisaged the act of writing, & how he would have liked his work to be read and understood. Thinking/reading through this poem helps me rethink how Celan’s (and, indeed many other) complex poems need to be read.

Celan, especially in his late poetry, insists on the importance of the word. This poem thematically foregrounds this point, yielding insights not only into Celan’s writing process, but also into the reading process. The work of poetry is to be done on the word itself, the word that is presented here as hollow, as a cave — an image that suggests immediately a range of connections with similar topoi throughout the oeuvre, from prehistoric caves to etruscan tombs. The word is nothing solid, diorite or opaque, but a formation with its own internal complexities and crevasses — closer to a geode, to extend the petrological imagery so predominant in Celan. In the context of this first stanza, however, the “panther skins” seem to point more towards the image of a prehistoric cave, at least temporarily, for the later stanzas retroactively change this reading, giving it the multi-perspectivity so pervasive to the late work.

These words need to be worked, transformed, enriched, in order to become meaningful. In this case the poem commands the poet to “line” them with animal skins, suggesting that something usually considered as an external covering is brought inside and turned inside-out. The geometry of this inversion makes for an ambiguous space, like that of a Klein bottle where inside and outside become indeterminable or interchangeable. These skins, pelts or furs also seem to be situated between something, to constitute a border of some sort, for the next stanza asks for the caves to be enlarged in at least two, if not four directions, i.e. “pelt-to and pelt-fro, / sense-hither and sense-thither.” This condition of being between is indeed inscribed in the animal chosen by Celan, via a multilingual pun (though he wrote in German, Celan lived in a French-speaking environment while translating from half a dozen languages he mastered perfectly): “between” is “entre” in French, while the homophonic rhyme-word “antre” refers to a cave; this “antre” or cave is inscribed and can be heard in the animal name “Panther.” (One could of course pursue the panther-image in other directions, for example into Rilke’s poem — and Celan’s close involvement with Rilke’s work is well documented.) Unhappily the English verb “lined” is not able to render the further play on words rooted in the ambiguity of the German “auskleiden,” which means both to line, to drape, to dress with, and to undress.

These “Worthöhlen,” in a further echo of inversion, give to hear the expression “hohle Worte”—empty words (The general plural for “Wort” is “Wörter,” but in reference to specific words you use the plural “Worte.”) Words, and language as such, have been debased, emptied of meaning — a topos that can be found throughout Celan’s work — and in order to be made useful again the poet has to transform and rebuild them, creating in the process those multiperspectival layers that constitute the gradual, hesitating yet unrelenting mapping of Celan’s universe. The third stanza thus adds a further strata to the concept of “Worthöhlen” by introducing physiological terminology, linking the word-caves to the hollow organ that is the heart. These physiological topoi appear with great frequency in the late books and have been analyzed in some detail by James Lyon[1], who points out the transfer of anatomical concepts and terminology, and, specifically in this poem, how the heart’s atria become the poem’s courtyards, the ventricles, chambers and the valves, drop doors. The poem’s “you,” as behoves a programmatic text, is the poet exhorting himself to widen the possibilities of writing by adding attributes, by enriching the original word-caves. The poem’s command now widens the field by including a further space, namely “wildnesses,” a term that recalls and links back up with the wild animal skins of the first stanza. Celan does not want a linear transformation of the word from one singular meaning to the next, but the constant presence of multiple layers of meaning accreting in the process of the poem’s composition. The appearance in the third stanza of these wildnesses also helps to keep alive the tension between a known, ordered, constructed world and the unknown and unexplored, which is indeed the Celanian “Grenzgelände,” that marginal borderland into which, through which and from which language has to move for the poem to occur.

But it is not just a question of simply adding and enlarging, of a mere constructivist activism: the poet also has to listen. The last stanza gives this command, specifying that it is the second tone that he will hear that is important. The poem itself foregrounds this: “tone” is the last word of the poem, constituting a whole line by itself while simultaneously breaking the formal symmetry of the text which had so far been built up on stanzas of two lines each. Given the earlier heart-imagery, this listening to a double tone immediately evokes the systole/diastole movement. The systole corresponds to the contraction of the heart muscle when the blood is pumped through the heart and into the arteries, while the diastole represents the period between two contractions of the heart when the chambers widen and fill with blood. The triple repetition on the need to listen to the second tone thus insists that the sound produced by the diastole is what is of interest to the poet.

Systole/diastole, a double movement most basic to life, thus important to be aware of, and made visible here as “the heart” of the poem, & giving the reader in the process a how-to-read in a double movement of reading/writing or of writing/reading.

–Pierre Joris

[1] Lyon, J. K. (1987b). “Die (Patho-)Physiologie des Ichs in der Lyrik Paul Celans.” Zeitschrift für Deutsche Philologie.106(4)

Breathturn to Timestead: The Collected Later Poems of Paul Celan, edited, translated and with commentaries by Pierre Joris. Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2014.

Pierre Joris is the author of more than 40 books of poetry, essays, and translations including Poasis: Selected Poems 1986–1999 (Wesleyan, 2001) and A Nomad Poetics: Essays (Wesleyan, 2003). He was co-editor of Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern and Postmodern Poetry and has published English translations of Celan, Tzara, Rilke and Blanchot, among others. You can read his blog here.

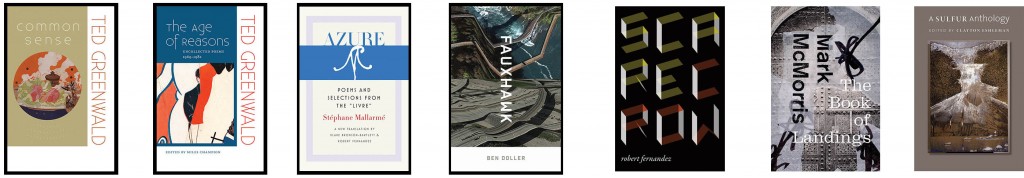

Be sure to check out our new poetry!

Common Sense (Ted Greenwald)

Age of Reasons: Uncollected Poems 1969–1982 (Ted Greenwald)

Azure: Poems and Selections from the “Livre” (Stéphane Mallarmé)

Fauxhawk (Ben Doller)

Scarecrow (Robert Fernandez)

The Book of Landings (Mark McMorris)

A Sulfur Anthology (edited by Clayton Eshleman)