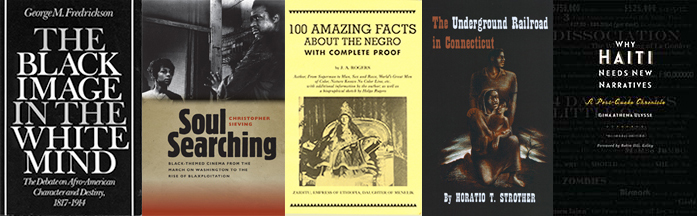

In honor of Black History Month, this week’s Throwback Thursday sheds light on some of the African American and Caribbean intellectual and scholarly works published by Wesleyan University Press. Not only has Wesleyan published a number of scholarly works that fall into the category of African American and Caribbean studies, we also recently became the distributor of works by the formative Jamaican-American author and journalist, J.A. Rogers. In keeping with Wesleyan’s tradition, we are very excited about a groundbreaking book coming this May, Why Haiti Needs New Narratives, in which Wesleyan anthropology professor Dr. Gina Athens Ulysse explores many facets of the aftermath of the devastating earthquake that struck Haiti in 2010.

There are many highlights in Wesleyan’s African American and Caribbean Studies list, from film scholar Christopher Sieving’s Soul Searching: Black-Themed Cinema From the March On Washington to the Rise of Blaxploitation, which examines African American commercial cinema prior to the advent of more commonly known “blaxploitation” movies, to seminal older works by renowned historian George M. Fredrickson, The Black Image in the White Mind and The Arrogance of Race.

Today’s excerpt is from Horatio T. Strother’s The Underground Railroad in Connecticut. Though it was published in 1962, the book maintains its relevance in today’s conversations about the development of slavery and abolitionism in America. Strother’s book is based on the masters thesis he wrote as a graduate student at the University of Connecticut. Having held a long fascination with what, as a child, he’d imagined as “a big train roaring through a long tunnel,” he persisted with the project, despite being told that there was not enough information available to form a cohesive thesis. Strother defied this warning and went on to uncover new material on the subject. At a time when the oral tradition was not held in high regard by mainstream scholars, Strother made a bold decision to include oral accounts of first generation descendants of people involved in the shepherding of escaped slaves. Sadly, Strother died in a tragic swimming accident at age 44, cutting short a promising academic career.

In Chapter 3 of the book, Strother describes the lives of three slaves who escaped to Connecticut. The first is William Grimes, whose life in Connecticut and eventual decision to purchase his own freedom is described in the following excerpt.

from The Underground Railroad in Connecticut:

But Grimes found it difficult to make a living in eastern Connecticut, so he returned to New Haven. There he found work at Yale College, shaving, barbering, “waiting on the scholars in their rooms,” and doing odd jobs for other employers on the side. Six or eight months later he heard that a barber was needed at the Litchfield Law School—Tapping Reeve’s famous establishment—and there he went in the year 1808. He became a general servant to the students and was also active as a barber, earning fifty or sixty dollars per month. “For some time,” he said, “I made money very fast; but at length, trading horses a number of times, the horse jockies would cheat me, and to get restitution, I was compelled to sue them; I would sometimes win the case; but the lawyers alone would reap the benefit of it. At other times, I lost my case, fiddle and all, besides paying my attorney…. Let it not be imagined that the poor and friendless are entirely free from oppression where slavery does not exist; this would be fully illustrated if I should give all the particulars of my life, since I have been in Connecticut.”

Back in New Haven in the year 1812 or 1813, Grimes met and soon married Clarissa Caesar, a colored girl whom he called “the lovely and all accomplished.” She was also a “lady of education,” teaching him all the reading and writing he ever knew. Because his situation was not entirely safe—he was still a runaway slave and still, before the law, his master’s property—Grimes and his bride returned to “the back country” of Litchfield, where they bought a house and settled down. And just as he had feared, his owner eventually learned of his whereabouts and sent an emissary, a brisk and rude fellow called Thompson, to reclaim him. This man confronted the fugitive with a plain choice: he could buy his freedom, or Thompson would “put him in irons and send him down to New York, and then on to Savannah.” Grimes described his state of mind and his subsequent actions as follows:

To be put in irons and dragged back to a state of slavery, and either leave my wife and children in the street, or take them into servitude, was a situation in which my soul now shudders at the thought of having been placed. … I may give my life for the good or the safety of others, but no law, no consequences, not the lives of millions, can authorize them to take my life or liberty from me while innocent of any crime. I have to thank my master, how ever, that he took what I had, and freed me. I gave a deed of my house to a gentleman in Litchfield. He paid the money for it to Mr. Thompson, who then gave me my free papers. Oh! how my heart did rejoice and thank God.

Thus William Grimes became a free man, to live out the rest of his long life as his own man in a free state. Yet, as he came to set down his memoirs in later years, he viewed the condition of slavery and the condition of freedom in a somewhat ambivalent light:

To say that a man is better fed, and has less care [in slavery] than in the other, is false. It is true, if you regard him as a brute, as destitute of the feelings of human nature. But I will not speak on the subject more. Those slaves who have kind masters are perhaps as happy as the generality of mankind. They are not aware what their condition can be except by their own exertions. I would advise no slave to leave his master. If he runs away, he is most sure to be taken. If he is not, he will ever be in the apprehension of it; and I do think there is no inducement for a slave to leave his master and be set free in the Northern States. I have had to work hard; I have often been cheated, insulted, abused and injured; yet a black man, if he will be industrious and honest, can get along here as well as any one who is poor and in a situation to be imposed on. I have been very fortunate in life in this respect. Notwithstanding all my struggles and sufferings and injuries, I have been an honest man.

Read the rest of Chapter 3 here to learn more about Grimes, as well as two other former slaves who utilized the Underground Railroad.

We hope our readers will join us in celebrating Black History Month this February, with some great books!