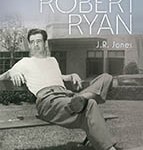

The Lives of Robert Ryan provides an inside look at the gifted, complex, intensely private man whom Martin Scorsese called “one of the greatest actors in the history of American film.” The son of a Chicago construction executive with strong ties to the Democratic machine, Ryan became a star after World War II on the strength of his menacing performance as an anti-Semitic murderer in the film noir Crossfire. Over the next quarter century he created a gallery of brooding, neurotic, and violent characters in such movies as Bad Day at Black Rock, Billy Budd, The Dirty Dozen, and The Wild Bunch.

His riveting performances expose the darkest impulses of the American psyche during the Cold War. At the same time, Ryan’s marriage to a liberal Quaker and his own sense of conscience launched him into a tireless career of peace and civil rights activism that stood in direct contrast to his screen persona. Drawing on unpublished writings and revealing interviews, film critic J.R. Jones deftly explores the many contradictory facets of Robert Ryan’s public and private lives, and how these lives intertwined in one of the most compelling actors of a generation.

For more information on Robert Ryan, visit the book’s website.

J.R. Jones is an award-winning film critic and editor for the Chicago Reader. His writing has appeared in New York Press, Kenyon Review, Da Capo Best Music Writing, and Noir City. He lives in Chicago.

Catch a screening of The Set-Up at Chicago’s Music Box Theatre, including a Q&A with the author and Lisa Ryan, daughter of Robert Ryan. Purchase your book and film ticket in advance and save $2 off the cover price, courtesy of The Book Cellar.

You can also catch J.R. Jones at Chicago Tribune’s Printers Row Lit Festival in June.

Enjoy clips from Robert Ryan films, below.

Praise for The Lives of Robert Ryan:

“As self-effacing yet as solid and as ethically engaged as Robert Ryan himself, J.R. Jones offers a comprehensive and sensitive chronicle of one of the giants of American movie acting.”

—Jonathan Rosenbaum, author of Movie Wars“Too many critical biographies lurch back and forth between biography and criticism. Jones weaves the criticism in the biographical fabric, and the finished product has a very friendly mien—The Lives of Robert Ryan is a book you will want to spend time with.”

—Kent Jones, author of Physical Evidence: Selected Film Criticism“J.R. Jones’s meticulous, revealing book on Robert Ryan places the actor’s life and career against the turbulent politics of the Cold War and the Red Scare in Hollywood. Jones is especially adept at moving between the life and the work, the films and their contexts. He introduces political history throughout, in ways that are both relevant and revelatory.”

—Foster Hirsch, author of The Dark Side of the Screen: Film Noir“The Lives of Robert Ryan is a well-written, insightful biography on an important Hollywood actor who is finally getting the attention he deserves. Ryan was a fearless liberal who embraced controversial causes during a time when most Hollywood stars remained apolitical. Even many film scholars are unaware of this aspect of Ryan’s career. This biography emphasizes it.”

—Richard B. Jewell, author of RKO Radio Pictures: A Titan is Born

Publication of this book is funded by the Beatrice Fox Auerbach Foundation Fund at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.