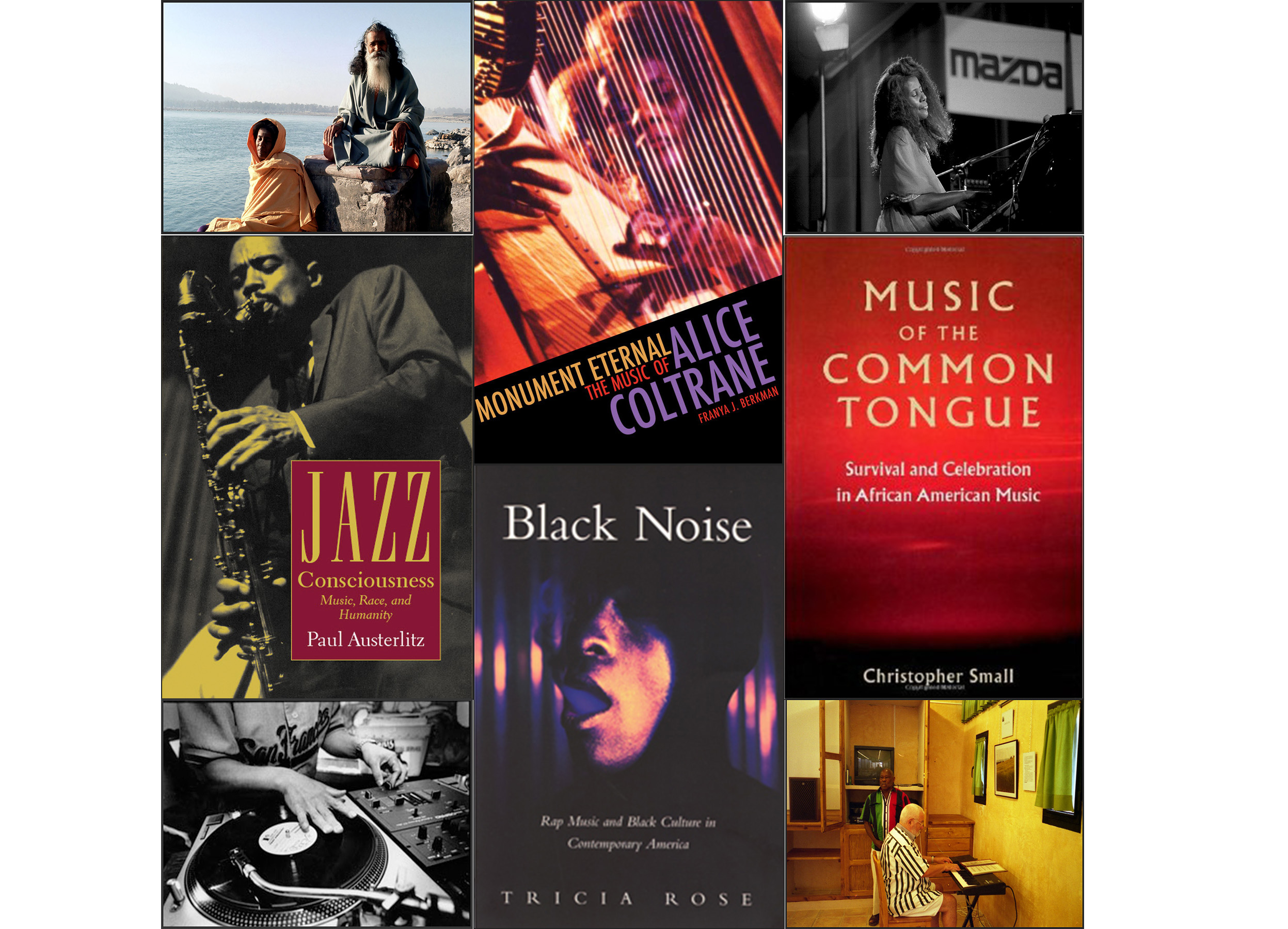

This week’s Throwback Thursday post, the final post for our Black History Month series, features one of Wesleyan University Press’ best-selling titles, Tricia Rose’s Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. Rose’s book is one among many published by Wesleyan on African American music and musicians. Other books include Monument Eternal: The Music of Alice Coltrane, by Franya J. Berkman, on the life and work of Alice Coltrane as a composer, improviser, and guru; the classic text Music of the Common Tongue: Survival and Celebration in African American Music, by Christopher Small, who explored the origins, nature, and function of music in human life; and Jazz Consciousness: Music, Race, and Humanity, by Paul Austerlitz, who provides a scholarly argument to support the theory of a wide-reaching jazz consciousness—an aesthetic of inclusiveness—considering jazz within the African diaspora and in varying transnational scenes, from Finland to the Dominican Republic.

In the following excerpt, Rose discusses the deep political implications present in rap music:

Rap music is, in many ways, a hidden transcript. Among other things, it uses cloaked speech and disguised cultural codes to comment on and challenge aspects of current power inequalities. Not all rap transcripts directly critique all forms of domination; nonetheless, a large and significant element in rap’s discursive territory is engaged in symbolic and ideological warfare with institutions and groups that symbolically, ideologically, and materially oppress African Americans. In this way, rap music is a contemporary stage for the theater of the powerless. On this stage, rappers act out inversions of status hierarchies, tell alternative stories of contact with police and the education process, and draw portraits of contact with dominant groups in which the hidden transcript inverts/subverts the public, dominant transcript. Often rendering a nagging critique of various manifestations of power via jokes, stories, gestures, and song, rap’s social commentary enacts ideological insubordination.

In contemporary America, where most popular culture is electronically mass-mediated, hidden or resistant popular transcripts arc readily absorbed into the public domain and subject to incorporation and invalidation. Cultural expressions of discontent are no longer protected by the insulated social sites that have historically encouraged the refinement of resistive transcripts. Mass-mediated cultural production, particularly when it contradicts and subverts dominant ideological positions, is under increased scrutiny and is especially vulnerable to incorporation. Yet, at the same time, these mass-mediated and mass-distributed alternative codes and camouflaged meanings are also made vastly more accessible to oppressed and sympathetic groups around the world and contribute to developing cultural bridges among such groups. More over, attacks on institutional power rendered in these contexts have a special capacity to destabilize the appearance of unanimity among powerholders by openly challenging public transcripts and cultivating the contradictions between commodity interests, (“Docs it sell? Well, sell it, then.”)and the desire for social control (“We can’t let them say that.”) Rap’s resistive transcripts arc articulated and acted out in both hidden and public domains, making them highly visible, yet difficult to contain and confine. So, for example, even though Public Enemy know pouring it on in metaphor is nothing new, what makes them “prophets of rage with a difference” is their ability to retain the mass-mediated spotlight on the popular cultural stage and at the same time function as a voice of social critique and criticism. The frontier between public and hidden transcripts is a zone of constant struggle between dominant and subordinate groups. Although electronic mass media and corporate consolidation have heavily weighted the battle in favor of the powerful, contestations and new strategies of resistance are vocal and contentious. The fact that the powerful often win does not mean that a war isn’t going on.

Rappers are constantly taking dominant discursive fragments and throwing them into relief, destabilizing hegemonic discourses and attempting to legitimate counter hegemonic interpretations. Rap’s contestations are part of a polyvocal black cultural discourse engaged in discursive “wars of position” within and against dominant discourses. As foot soldiers in this “war of position,” rappers employ a multifaceted strategy. These wars of position are not staged debate team dialogues; they are crucial battles in the retention, establishment, or legitimation of real social power. Institutional muscle is accompanied by social ideas that legitimate it. Keeping these social ideas current and transparent is a constant process that sometimes involves making concessions and adjustments. As Lipsitz points out, dominant groups “must make their triumphs appear legitimate and necessary in the eyes of the vanquished. That legitimation is hard work. It requires concession to aggrieved populations…it runs the risk of unraveling when lived experiences conflict with legitimizing ideologies. As Hall observes, it is almost as if the ideological dogcatchers have to be sent out every morning to round up the ideological strays, only to be confronted by a new group of loose mutts the next day.” Dominant groups must not only retain legitimacy via a war of maneuver to control capital and institutions, but also they must prevail in a war of position to control the discursive and ideological terrain that legitimates such institutional control. In some cases, discursive inversions and the contexts within which they are disseminated directly threaten the institutional base, the sites in which Gramsci’s wars of maneuver are waged.

In contemporary popular culture, rappers have been vocal and unruly stray dogs. Rap music, more than any other contemporary form of black cultural expression, articulates the chasm between black urban lived experience and dominant, “legitimate” (e.g., neoliberal) ideologies regarding equal opportunity and racial inequality. As new ideologi al fissures and points of contradiction develop, new mutts bark and growl, and new dogcatchers are dispatched. This metaphor is particularly appropriate for rappers, many of whom take up d-Og as part of their nametag (e.g., Snoop Doggy Dog, Tim Dog, and Ed O.G. and the Bull dogs). Paris, a San Francisco-based rapper whose nickname is P-dog, directs his neo-Black Panther position specifically at ideological fissures and points of contradiction:

P-dog commin’ up, I’m straight low

Pro-black and it ain’t no joke

Commin’ straight from the mob that broke shit last time,

Now I’m back with a brand new sick rhyme.

So, black, check time and tempo

Revolution ain’t never been simple

Submerged in winding, dark, low, bass lines, “The Devil Made Me Do It” locates Paris’s anger as a response to white colonialism and positions him as a “low” (read underground) voice backed up by a street mob whose commitment is explicitly pro-black and nationalist. A self proclaimed supporter of the revived and revised Oakland-based Black Panther movement, Paris (whose logo is also a black panther) locates himself as a direct descendent of the black panther “mob that broke shit last time” but who offers a revised text for the nineties. Paris’s opening line, “this is a warning” and subsequent assertion, “So don’t ask next time I start this, the devil made me do it,” along with his direct address to blacks “so, black, check time and tempo,” suggest a double address both to his extended street mob and to those whom he feels are responsible for his rage. “Check time and tempo” is another double play. Paris, a member of the Nation of Islam (NOI) is referring to the familiar NOI cry, “Do you know what time it is? It’s nation time!” and the “time and tempo” based nature of his electronic, digital musical production. Later, he makes more explicit the link he forges between his divinely inspired digitally coded music and the military style of NOI programs:

P-dog with a gift from heaven, tempo 116.7

Keeps you locked in time with the program

When I get wild I’ll pile on dope jams.

Speaking to and about dominant powers and offering a commitment to military mob-style revolutionary force, P-dog seems destined to draw the attention of Hall’s ideological dogcatchers. Although revolution has never been simple, it seems clear to Paris that not only will it be televised, it will have a soundtrack, too.